Chapter 11: OUT OF SPACE: Nostalgia for Giant Steps and Final

Frontiers

Dates like “1999”, “2000”, “2001” set off special reverberations-- not just for the s.f. fans among us but for plenty of regular folk too. Even now, when we should have grown blasé about living in the 21st Century, the dates still have a faint futuroid tang that makes the act of, say, writing out and dating a cheque or a form feel slightly eerie, tingling with a poignant trace of what-should-have-been

“The most cited studies in a field used to be the product of lone geniuses... but the best research now emerges from groups. One explanation for this shift is the necessity of interdisciplinary collaborations: the most complex problems can no longer be solved by people with expertise in a single field. However, there is another related possibility: science is getting harder. Last year, Samuel Arbesman, a research fellow at Harvard Medical School, published a paper in Scientometrics that documents the increasing difficulty of scientific discovery. By measuring the average size of discovered asteroids, mammalian species and chemical elements, he was able to show that, over the last few hundred years, these three very different scientific fields have been obeying the exact same trend: the size of what they discover has been getting smaller.

Lehrer compares to this discovery-declining-rate theory to Tyler Cowen’s idea of a “great stagnation”, which argues that “that our current economic problems are rooted in a larger innovation failure, as the outsized gains of the 20th century (in which living standards doubled every few decades) have given way to a growth plateau... the American economy has enjoyed lots of low-hanging fruit since at least the seventeenth century: free land; immigrant labor; and powerful new technologies. Yet during the last forty years, that low-hanging fruit started disappearing and we started pretending it was still there. We have failed to recognize that we are at a technological plateau and the trees are barer than we would like to think.”

Miniaturization of communications technology

"Politically, militarily, economically, the decade was defined by disappointment after disappointment—and technologically, it was defined by a series of elegantly produced events in which Steve Jobs, commanding more attention and publicity each time, strode on stage with a miracle in his pocket....

"Apple made technology safe for cool people—and ordinary people. It made products that worked, beautifully, without fuss and with a great deal of style. They improved markedly, unmistakably, from one generation to the next—not just in a long list of features and ever-spiraling complexity (I’m looking at you, Microsoft Word), but in simplicity...

"Steve Jobs was the evangelist of this particular kind of progress—and he was the perfect evangelist because he had no competing source of hope.”

Crouch presents as a kind of privatized version of utopianism or faith:

"This is the gospel of a secular age. It has the great virtue of being based only on what we can all perceive—it requires neither revelation nor dogma. And it promises nothing it cannot deliver—since all that is promised is the opportunity to live your own unique life.... The world—at least the part of the world in our laptop bags and our pockets, the devices that display our unique lives to others and reflect them to ourselves—will get better. This is the sense in which the tired old cliché of “the Apple faithful” and the “cult of the Mac” is true. It is a religion of hope in a hopeless world...

The three decades following the end of the Second World War in 1945 had been one long surge of economic growth, technological innovation, and cultural energy, kickstarted by the war itself and its massive mobilization of populations and resources, the state’s vastly increased investment in science and technology, and the peculiar fact that war raises a people’s morale by giving them a sense of purpose and unity (rates of mental illness declines markedly compared with peace time). That postwar surge--and the consensus about the role of interventionist state power, the need for social welfare, and so forth--had begun to falter by the early Seventies.

The fuel crisis of late 1973 was the augur of a massive reality check. Some analysts see that year as the end of a “long Sixties” that began circa 1957. Except that the energies liberated in the post-war period (during which the high metabolic rate of the economy encouraged a mood of future-tilted euphoria and a mania for all things new and progressive) and which reached a climax with the Sixties, didn’t come to a halt punctually in synch with the economic slow-down. There was a kind of time lag, a disparity between economic base and cultural superstructure, which is one reason why the 1970s were a period of such turmoil and polarization. “The left”, understood in the broadest sense, headed further outwards on their trajectory of liberalization and radicalism; the right retrenched in the name of “realism” and the restoration of pre-Sixties morality, a.k.a. family values.

One way of understanding what happened in the Eighties is to see this backlash as partly a delayed response to an economic and sociocultural slow-down that occurred slightly earlier, in the mid-Seventies. Ppostmodernism and retro-recycling ruled popular culture, while politically the presiding spirits of the era, Thatcher and Reagan, were dedicated to restoration of an older order and the rolling back of the gains of the 1960s, a decade they reviled and pinpointed as “where it all went wrong”.

It can hardly be a coincidence that at precisely the point at which both the ideals and the actual gains of the Sixties were being concertedly discredited and undermined, that the Sixties became a presence again in popular culture. Sometimes as empty pastiche (Motown and Stax revivalism of myriad stripes, Prince’s faux-psychedelia circa “Raspberry Beret”, Jesus & Mary Chain), but sometime as surrogate and succor, a wistful harking back to a better time undertaken in impotent defiance of the Eighties (The Smiths, REM and a thousand Byrds-influenced college rock bands)

Jean B saw it as a specifically European malaise: “we are condemned to the imaginary and nostalgia for the future” whereas, he argued, Americans had “realized fiction” and lived in the future, now.

from page 184 of The Book of Disquiet:

"And yet what nostalgia for the future* if I let my ordinary eyes receive the dead salutation of the declining day! How grand is hope’s burial, advancing in the still golden hush of the stagnant skies! What a procession of voids and nothings extends over the reddish blue that will pale in the vast expanses of crystalline space!

Ah, the high and larger moon of these placid nights, torpid with anguish and disquiet! Sinister peace of the heavens’ beauty, cold irony of the warm air, blue blackness misted by moonlight and reticent to reveal stars."

*an alternate version reads: “what regret that I’m not someone else”

**an alternate version reads: “incipient impatience with myself”

You get similar flavors of profoundly bored restlessness and nameless omnisexual longing in the songs of Morrissey, but in his case mixed up with actual nostalgia in the traditional, past-directed sense. Pessoa's Book of Disquiet, Buzzcocks's songs like "Nostalgia" and "Why Can't I Touch It", Smiths songs like "Still Ill"--these are all testaments of exile. Ernst Bloch, the great Marxist theorist of utopia, writes about "the topically still unidentified no-where whither music leads." Music represents pure transcendence and transport; it's the way out from the drear of here-and-now.

Futurama

Partly reflecting Trevor Horn's love of science fiction, from songs like "Living in the Plastic Age" to "Video Killed the Radio Star" (obliquely inspired by a J..G Ballard short story), "I Love You (Miss Robot)" , "Astroboy" and "Johnny On the Monorail".

Retrofuturism in pop culture and pop music / a preliminary attempt at categorization

Just look at Kraftwerk, with their “We Are the Robots” shtick (the band replaced onstage by automatons), their back projected imagery redolent more of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis than NASA in the Seventies. Critiquing the Kraftwerk-indebted New Romantic (a.k.a. Futurist movement) in English pop, which encompassed everything from Gary Numan to Visage, in 1980 Martyn Ware of The Human League declared “it’s a very old fashioned view of futurism, which is like people walking about like Michael Rennie out of The Day the Earth Stood Still. That’s not futurism, that’s more nostalgia than anything else.” But The Human League were themselves a mish-mash of genuine modernism and retro-futurism. The band’s two musicians, Ian Craig Marsh and Martin Ware grappled with the possibilities (and limitations) of state-of-art synthesizers, plunging deep into the technical nitty-gritty of building drum sounds out of blurts of electronic noise. But the band’s image and aura largely stemmed from singer Phil Oakey, a science fiction nut who wrote lyrics inspired by Philip K. Dick and black holes, and from Adrian Wright, a Thunderbirds-fan with a highly developed sense of kitsch, who as Director of Visuals was in charge of creating the slides projected behind the band at gigs.

So what are we actually saying when we talk of music in terms of futurism or say something sounds futuristic? What do electronica musicians mean when they declare they’re “living for the future” (Omni Trio) or boast “we bring you the future” (Noise Factory) or even name themselves things like Phuture? (This “ph”, as used by the inventors of acid house, Phuture, soon became the techno signifier of futurity, a rave code carried on by Photek, Phuturistix, and many more). So much electronic dance music was received and felt and written about as future music. The idea is that the underground is the vanguard, the forward sector of pop music, bringing you right now the ideas that will eventually become the common everyday matter of mainstream pop. But surely, by definition, if these sounds are happening-right now, then how can they be from or of the future? In quest of some kind of clarity, I here sketch a three-way conceptual division:

Futurism

Referring to artists who make an overt ideology out of their aspiration to make tomorrow’s music today, and includes many people in techno, but also groups like The Young Gods, the late Eighties Swiss band who sounded “rock” and had a human drummer but whose actual sound was built from samples of heavy metal, punk, and classical music. Or earlier, the Art of Noise, who pioneered the use of the Fairlight sampler in pop. Both of these groups are not only futurists but have an intellectual debt to the artistic movement Futurism, which AoN make crystal clear with their name, a homage to Luigi Russolo’s The Art of Noises, the musical manifesto of the Italian Futurists.

Futuristic

Describing groups who play with science fiction imagery, an established set of signifiers and associations that relate to a tradition of envisaging (or sonically imagining) the Future. Add N to (X) were notable exponents of this approach in the late Nineties. Scholars of electronic music history, they built their own canon that included the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Throbbing Gristle, Wendy Carlos, and keyboard-dominated prog rockers like Egg, but pointedly excludes Kraftwerk along with the entirety of post-rave electronica. There’s a definite tinge of retro-futurism here, although Add N to (X)’s Ann Shelton characterized the approach as not so much nostalgia as pragmatism, an acceptance that futurism had become its own tradition: “It's a matter of knowing exactly how and what music has ever been made, and knowing what state the music world is in and understanding the futility of trying to do something new as opposed to just doing it without trying.”

Lillian Roxon writing in 1969 about the future of rock (in Lillian Roxon's Rock Encyclopedia)

Raymond Williams, the godfather of cultural studies, classified cultural artifacts or styles as either residual or emergent. Residual, as you’d expect, referred to tradition, folklore, roots; emergent, equally predictably, designated the progressive, forward-looking, innovative. By and large, music that has any impact on the wider culture beyond the academy or the experimental ghetto necessarily involves a mixture of residual and emergent. Arguably, the futuroid aspect has to be tempered with or grounded in elements of tradition for the music to be enjoyable or even tolerable. A wholly Futuroid music might be as aurally indigestible as Marinetti’s pr oposed Futurist replacement for pasta: a dish of perfumed sand.

The strange thing is that as a fan and explorer of music, I’ve been ardently chasing the sonic equivalent of “perfumed sand” for some years now, seeking out music that presents the utmost challenge to my ability to respond to it as musical. As discussed in this chapter, over the last 13 years or so, with mounting intensity, I’ve become obsessed with the avant-garde classical music of the second half of the 20th Century, the post-WW2 frontier of musique concrete and electronic composition opened up by figures like Karlheinz Stockhausen, the two Pierres (Henry and Schaeffer), Morton Subotnik, Luigi Nono, and many more.

Retromodernism

The Noughties saw a new boom in retro-modernism but the interest was significantly less surface-oriented than the Eighties recycling of Constructivist and Futurist graphics. From endless museum retrospectives of Futurism, Dada, Suprematism, et al, to books like Manifesto: A Century of Isms (an anthology heavily slanted to the first three decades of the 20th Century, what compiler Mary Ann Caws regarded as the golden age of manifesto-making) to conferences like the Tate's late 2009 Don't Look Back: Radical Thinkers and the Arts Since 1909, there has renewed interest in "combative, collective movements of innovation" (Perry Anderson) of the kind that virtually disappeared from the scene with the onset of postmodernity.

Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool, for whose opening Pierre Henry composed Messe De Liverpool

below is Saint Basil's in LA

Ruins of radicalisms bygone

The anti-utopian critic Christopher Booker uses the term "nyktomorph" or night-shape, a notion popular with 19th Century Romantic poets, to talk about the way so many people in the Sixties chased the mirage of the new. In his book The Neophiliacs, a kind of obituary for the Sixties, Booker compares nyktomorphs with ruins, that other obsession of poets like Wordsworth: both are expressions of the "the great Romantic emotion of nostalgia, a fixing of the mind on something unattainable…"

Cold War Design exhibition

The gist of the exhibition was a different twist on the modernist idea of the inseparability of aesthetics and politics: here it was the superpowers who were jousting, staking the case for which country and creed had the stronger claim to the future. In this contest between consumerism and communism, conveniences versus cosmonauts, the military subtext of the word "avant-garde" (it means a scouting party, whose job is to go in advance of the main army and skirmish, to initiate conflict) emerged in a new light. Modernism resumed in full force after World War Two, but it no longer took the form of signifying epater le bourgeois raids on the mainstream by a marginal elite; it was quite close to the official high culture of the developed world, Western and Eastern. Not only were the would-be revolutionaries of the early 20th Century turned into a new school of Old Masters by museums and curators, dealers and collectors, but the contemporary resurgence of modernist art (abstract expressionist painting, non-figurative sculpture, minimalism and colour-field art) became the preferred decor of corporations and public institutions. And the ideas filtered down into everyday life, merging with the new materials (the ever-expanding array of plastics, fibre glass) and reaching ordinary people's homes in the form of sleek radiograms, streamlined kettles, and elegantly austere chairs. Even nuclear defence bunkers looked cool.

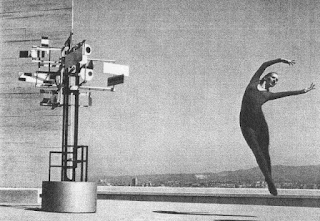

Wandering around Cold War Modern, gawping at, the gaudy whirling kinetic sculptures of Nicolas Schöffer, and the (sadly, mostly on paper) visions of Archigram, it was hard not to feel wistful about this lost future. Particularly affecting were the images of television towers like the Post Office Tower in London and its Eastern Bloc equivalents, which the exhibition argued were the 20th Century equivalent of Medieval cathedrals, expressions of the spirit of the age: a Marshall McLuhan-style techno-mysticism saw in science a kind of unfolding destiny, "an inherent theocratic logic". These thrillingly vertical teletowers were the spires of a secular surrogate for religion: the global village, the world sheathed by McLuhan's "cosmic membrane" of electronic transmissions.

Philips Pavilion / Poeme Electronique

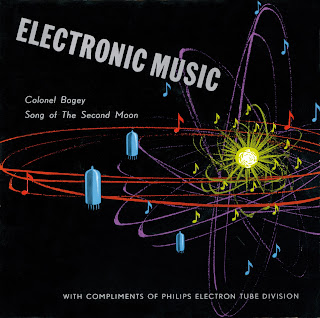

Philips research facility Natlab / Badings, Dissevelt, Raaijimakers

The Silver Records: Philips's series Prospective 21e Siecle

My piece for the Wire on my obsession with Prospective 21e Siecle - the artwork and the music

The holy grail, which came into my hands very recently, thanks to the remarkable generosity of a benefactor

a lot more Prospective 21 e silver sleeves at the end of these footnotes

Collecting post-WW2 electronic and musique concrete

Even the fonts used look august and solemn. The packaging suits the contents perfectly, because each of these painstakingly constructed sound-works is a monument to a future that never arrived. The whole package drips with pathos, but that’s not all--there’s a certain romance and honor, too. This plangent mix of emotions, stirred by the artifact as a tangible package rather than just the sonics in isolation, is what enthralls me about the recordings of this era. I treasure these LPs like other people cherish antiques. Instead of being relics of a nobler time, these are talismans of futurity foregone. Some vintage avant-classical records are literally antiques, chased by hunter-collectors, the rarest fetching huge sums on eBay and Gemm. Occasionally you’ll see them high on the wall in a used vinyl store, placed out of reach to deter cash-poor obsessives from attempting a grab-and-run. Too much of a tightwad to collect the really rare stuff, I nonetheless get a shiver when I consider that the most costly recording I own is over half a century old: Panorama of Musique Concrete, featuring early works by Schaeffer, Henry, and Philippe Arthuys, released by London/Ducretet-Thomson in 1956

I started picking up the old records like crazy--way faster than I could listen to them, in fact. Our first child had arrived, and weaving abstract, atonal electronics into everyday listening became much harder. In truth, my ears weren’t up to it much of the time, as parental duties took their toll. So the vinyl piled up in the living room, much of it unplayed, a testament to this strange new obsession.

[found this for a dollar in the yard sale at the apartment block over the road from us in the East Village]

As well as the concrete and electronic stuff, I was picking up avant-classical compositions based on the traditional orchestral palette of acoustic instruments and the human voice. Some of this choral and operatic music, by Ligeti, Berio, and Nono, was as eerie and out-there as the electronic stuff. I also checked out the avant-classical mini-genre of percussion music too, which seemed promising but somehow managed to be both underwhelming and hard-going. As imposing and clangorous as these percussion ensembles sounded, the music wasn’t minds-eye activating like the tape and synthesizer-based work of your Morton Subotniks and Bernard Parmegianis. The latter set all kinds of alien color-shapes and impossible geometries reeling inside my head; the percussion-only work just conjured the mental picture of a bunch of guys in suits clutching mallets, ruffled and sweaty. But then drums and percussion are old instruments, as familiar as violins and tubas, and the sounds they make are indelibly linked to a vocabulary of performance gestures. Whereas the voice is arguably is our most ancient technology for sound-synthesis; more than almost any acoustic instrument, it has a capacity to produce sounds that seem disembodied, infrahuman. Perhaps that’s why the unsettling and otherworldly choral music by Ligeti could hold its own with the purely electronic and tape work, music built with newly invented instruments.

Classical music veered off in a different path

There was a gradual shift back towards tonality and traditional acoustic instrumentation. Partly this was a matter of fashion. The “next big thing” was minimalism. Some of its pioneers had experimented with tape and electronics themselves, like Steve Reich with his famous loop-delay pieces “It’s Gonna Rain” and “Come Out”, and Terry Riley with his electric keyboard-driven A Rainbow in Curved Air. But as the minimalist approach emerged, its emphasis was hypnotic repetition rather than the ear-ambushing sonic singularities of the elektronische and concrete composers. Above all, the new breed of composers veered from dissonance back to consonance. There was a common impulse towards “remusicalizing and rehumanizing composition”, a desire to return to “functional harmony, motor rhythm”, an interest in generating complexity out of simplicity, and an attraction to an overall atmosphere of euphonious euphoria that was in stark contrast with the “dark, tension-creating” and harrowed-sounding music associated with composers like Boulez (all quotes from Laurie Spiegel).

Why did electronics, contrete and the more atonal/abstract forms of composition for traditional instruments never find a receptive public? Noting how modernist art of every stripe (from abstract expressionist to post-Bauhaus architecture to Op Art to…) has successfully pervaded mainstream culture in a way that has far outstripped the infiltration rate of modernist music, the critic David Stubbs argues in his book Fear of Music that sound is intrinsically more invasive than the pictorial or plastic arts. There is something intimate about music, it surrounds our bodies and penetrates our inner being; as a result, atonality, dissonance, and abstraction trouble our psychic equilibrium far more profoundly than their equivalents in painting or sculpture. This is why the twelve-tone and serialist composers like Schoenberg and Webern were such an affront to the sensibilities of bourgeois classical music audiences in the early 20th Century. When harmony is disrupted or abandoned, our sense of the world as an ordered and potentially redeemable place is shattered. To most concert goers, this (original) new music was emotionally incomprehensible; listening to it felt a little like going insane. Often, it was about mental states of disquiet and anguish; Schoenberg himself used the word “nightmare” to describe his work. This helps explains why one of the few avenues by which 20th Century avant-classical would eventually infiltrate the mainstream was the scores to horror movies and thrillers: the hair-raising glissandi, nerve-jangling pizzicato flurries, and ominous surges of amorphous sonic murk lent themselves to dramatizing suspense and evoking atmospheres of paranoia, psychosis, delirium, corruption. In that context, their wrongness felt right. But listened to away from the silver screen, in the concert hall or home environment, this music was too distressing for most listeners.

Avant-garde versus après-garde

Innovators always get more prestige and attention than the people who come along and build on their foundation. You could argue that equally accomplished and impressive work is made by the successor artists. But the early work just seems to have a special aura, lacked by the après-garde of craftsman-like custodians who carry building on the foundations laid by others.

But what goes is going on in our heads when we go back through art-historical time to experience a breakthrough, when we clearly have lived most or all of our lives in a world that was broken-through into, where what was radical about the work is just normal and accepted? Even more mysterious is the way we return again and again to a piece or music or work of art that depends for its impact on unfamiliarity, the shock of the new.

Fredric Jameson has a theory about this works. What defines the modernist artwork, he says in A Singular Modernity, is a relationship to time. It enacts the break with the past forms of art within itself. "The interiorization of the narrative [of modernity/modernism]…" becomes an integral element of the artwork's fundamental structure. "The act of restructuration is seized and arrested as in some filmic freeze-frame" such that the modernist work "encapsulates and eternalizes the process as a whole."

What could that mean in music? Precisely a genre that involved a kind of suspended clash of sampling/digital processing with the analogue/hand-played, such that the uncanny time-warping of digital technique coexists with and permeates the hands-on, real-time musicianship. Thus breakbeat science captures the moment of superhumanisation, the funk of flesh-and-blood drumming (just eight seconds of G. Coleman's life-force from "Amen, My Brother") mutating into something beyond itself. Likewise with vocal science. Jameson, again: "the older technique or content must somehow subsist within the work as what is cancelled or overwritten, modified, inverted or negated, in order for us to feel the force, in the present, of what is alleged to have once been an innovation."

The shock of the new, eternalized.

Electronic and concrete captures the imagination of the world

It wasn’t just a highbrow thing, though, all the curiosity about this bold new frontier being opened up. Pop culture succumbed to the fascination too. The Beatles, already experimenting with techniques of tape-editing and sound-warping with help from George Martin and the white-coated technicians at Abbey Road Studios, became besotted by Stockhausen. The composer can be spotted amid the pantheon of Fab Four heroes depicted on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Lennon reputedly telephoned the composer repeatedly during 1967, to the point of becoming a phone pest; the following year he recorded an extended concrete piece, “Revolution No. 9” for 1968’s The Beatles a.k.a. The White Album, a blatant emulation of the German composer’s Hymnen and Gesang Der Junglige. At that point, several years before Wings and “Silly Love Songs”, Paul McCartney was, believe it or not, even more interested in the avant-garde than Lennon. He actually pipped his partner to the post by splicing together his own 15 minute concrete piece “Carnival of Light”, although that one was never officially released. Even George Harrison found time between noodling on his sitar to make an entire album’s worth of Moog synth noises, which was released as Electronic Sounds via Zapple, the experimental imprint of the Beatles’ label Apple.

Other long-haired freaks were infatuated with the strange new colors and shapes and trompe l’oreille spatial sorcery that could be achieved using synths and tape. Frank Zappa was a huge fan of Edgard Varese and plunged deep into concrete techniques on albums like Uncle Meat. After botching their debut album, The Grateful Dead decided the only way to capture their live intensity was to embrace the sound-sculpting potential of the studio. Painstakingly stitching together live tapes with studio experimentation, 1968’s Anthem of the Sun drew heavily on the avant-classical training of bassist Phil Lesh and pianist Tom Constanten, both of whom had studied under Luciano Berio at Oakland, California’s Mills College (whose Tape Center was home base for New Music composers like Pauline Oliveros and Morton Subotnik). On both sides of the Atlantic, there was a mini-genre of “psychetronic” (or even “electrodelic”) bands who abandoned the electric guitar in favor of oscillators, ring modulators and other primitive tools of sound-synthesis, groups like Silver Apples, Fifty Foot Hose, White Noise (which involved two members of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop), United States of America (whose Dorothy Moskowitz had studied with Otto Luening of the Columbian-Princeton Electronic Music Center).

Of all of these, Silver Apples were the closest to a full-tilt all-electronic rock band, being a duo of drummer Danny Taylor and vocalist/synth-player Simeon. The latter played a bank of oscillators and pedals and identifying so strongly with this self-assembled instrument-of-one he named it The Simeon. Silver Apples were a tripped-out entity in line with the guitar-based acid rock of the era; Simeon’s highly-strung incantations (lyrics like "oscillations, oscillations, electronic evocations...spinning magnetic fluctuations") came from the same acid-scorched mind-zone as Roky Erikson of the 13th Floor Elevators. But the duo’s late Sixties tracks contained in germ form the oscillator-riffs, pulse-sequences and frequency-arpeggios that make up the lexicon of Nineties techno.

In an eerie but apparently purely coincidental parallel, Silver Apples shared their name with Morton Subotnik’s Silver Apples of the Moon. They’d both ripped it off W. B. Yeats, from his poem "The Song of Wandering Aengus". Released in 1967, Subotnik’s album was possibly the highest profile electronic music work of the era, becoming an American bestseller in the classical music category. It was released by Nonesuch, the classical division of Elektra Records, by that point famous as the home of the Doors and Love, but originally a folk, blues and ethnic music label synonymous with artists like Judy Collins and The Shanty Boys. Nonesuch rapidly established itself as a haven for the electronic avant-garde, releasing classic works by Subotnik, Xenakis, Charles Dodge, Wuorinen’s aforementioned Pulitzer- winning Time’s Encomium, and many more. They also put out The Nonesuch Guide to Electronic Music, a box set with an album of electronic noises plus a detailed booklet, which became a best-seller, staying on Billboard for 26 weeks. The project was put together by Bernie Krause, an old folkie who’d played banjo in the Weavers but was now looking for a new direction in music, and Paul Beaver, a collector of antiquated synths like the Ondes Martinot and the Novachord who did effects work for B-movie pulp sci-fi movies like Invasion Of The Body Snatchers.

Elektra weren’t the only folkies who skipped the electric stage and went straight to electronic. The Folkways label released a whole series of musique concrete and electronic albums, including including Vaclav Nelhybel’s Outer Space, while Native American troubadour Buffy Sainte-Marie’s album Illuminations was slathered with analog synth daubings from Michael Czajkowski (composer of People the Sky)

later period Pierre Henry gets a bit psychedelicized

as does Morton Subotnik by the mid-70s

Electronic music and its association with space

As the years went by, Stockhausen seemed to get more and more potty for outer space, talking about how his music should be played outdoors, under the stars, or claiming that "whenever my music or a moment in my music transports a listener into the beyond - transcending time and space - he experiences cosmic dimensions," while cautioning that only a select lofty-minded few could achieve such "contact with the supra human world" via his music. Echoing Sun Ra, Stockhausen claimed his birthplace wasn’t a small town near Cologne but a planet in the solar system of Sirius. His 1976 symphony Sirius was actually premiered at a state-of-art planetarium, the Albert Einstein Spacearium in Washington, D.C.

2001, A Space Odyssey

Another story in Memories of the Space Age, “The Dead Astronaut” pivots around the image of the cosmonaut-as-cadaver, mummified in his own space suit, circling for decades in orbit and then burning up on re-entry, like a Viking warrior hero’s burial in reverse.

Perhaps keen to champion his own discovery-zone of "inner space" over "outer space" as science fiction's true realm, Ballard continued to bang away at this idea-- that the general public had quickly lost interest in the idea of space travel—in his interviews and essays over the ensuing decades. He described the NASA and Soviet space programmes as throwback to Jules Vernes, the last spasm of "a kind of nineteenth-century heavy engineering technology". In 1997’s “One Dull Step for Man”, Ballard even asserted that “a curious feature of the Space Age was its lack of any real spin-off, its failure to excite the public imagination, to influence fashion, consumer design or architecture. How different from the Thirties, when the great record-breaking attempts, the ever faster trains, planes and racing cars, exerted an enormous influence on consumer design from department stores to teapots.” Not only did he miss the impact of Sputnik and cosmonaut suits on Sixties ultramodernist fashion, but--having a notoriously weak ear for music, at he himself often admitted--he failed to notice the the pervasive life that the idea of outer space exploration had in popular music.

great expectations for the space race

Written in 1976, it looks ahead to 2000 and “the first of the really elaborate Bases, possibly of the hemispherical form which was so widely favoured by the much-derided but often far-seeing science fiction writers of the days before the Space Age began".

"Did we fly to the moon too soon" / premature explorations

A very interesting post here by Tom Ewing about the song "First Man In Space" by The All Seeing I - words by Jarvis Cocker, singing by Phil Oakey - which Ewing reads as the blues of the early adopter (a sort of astronautical version of "Losing My Edge", almost) .

With the rise of synthpop bands like the Human League , Soft Cell, and Depeche Mode, electronics lost its evocation of the future or of the cosmic beyond: their songs were grounded in the earthly realm of love, relationships, or seedy squalor, or the sweaty, sexed-up realm of discos and nightclubs.

But by the end of the 1980s, the electronic and the extraterrestrial were once more yoked together with the arrival of acid house and the rave explosion. Attached to London’s leading acid house club Land of Oz was the world’s first chill-out zone, a side-room where acid-fried ravers retreated to soothe their synapses with the ambient music spun by a deejay who went by the name Dr. Alex Paterson. He played a lot of electronic mindscape music, things like Rainbow Dome Musick by Steve Hillage, formerly of cosmic rock ensemble Gong. Then came The Orb, whose music contained a curious unresolved blend of longing for the cosmic sublime and a sense that the notion of space exploration itself somehow become slightly camp.

On the whole, though, what was striking about the whole Nineties rave-fueled electronic music resurgence was its absolutely earnest sense of futurism, which was shaped in large part by the computer and internet revolution and given extra open-hearted sincerity thanks to sheer volume of Ecstasy being ingested in those days. The cyberdelic imagery on flyers and record covers, the triptastic utopian talk in interviews, it all seems kitschy and sappy now, but at the time, it didn't.

Judith Berman’s "Science Fiction without the Future"

William Gibson - atemporality, the disappearance of the capital F Future, and the now-focus of his three post-2000 novels / Bruce Sterling's latest thoughts on Atemporal Condition

"I am a Time Lord, and from the future I ask you what is the difference

between Gibson’s

quote last night and John Lydon yelling “No future”?

"The concept that Science Fiction is losing the timeline – the vision of the future – because of the uncertainties of the present is a little frightening. It conjures some mythical version of the eighties, that mad sense of dislocation that comes with the concept of Armageddon. It is as if all the things we fear might kill us, that everything could end the world.

"What a terrible thought. Worse, the idea that it might stop us really thinking about the future. Foresight and futurism are now discussed almost singularly as reactive tools. We are asked to imagine future solutions, to guess the best answers to problems we face now.

"As a result, our futures are reactive. Our political and social maps are being framed as a consequence of today’s mistakes, not today’s possibilities. Our deferred pleasures are turning out to be sticking plasters.

"I started thinking this in bed. I was there for ten minutes, head buzzing with a thought – thoughts – about the future.

"I kissed Anne goodnight, got out of bed, put my iPhone in the LEGO Mobile, and opened Spotify. I’m playing Treats, typing on my wireless keyboard. I feel a little as if my doing all of these things has distilled my year into a handful of actions. I try and look ahead.

"I can Google some of the samples on the album I’m listening to. I can discover that that blessed out beat sat underneath “Rill Rill” comes courtesy of Parliament. I can call up Funkadelic, scrobble it, dig around for a recommendation, move sideways, maybe to some De La Soul breaks. I can hear how these bands lay foundations for the music that comes next, whether they seep through as samples, guest vocalists or just through the speaker stacks.

"If I want I can dissect the guts of “Stylo” and pull it into the perfect playlist.

"I have infinite opportunities to explore the past like this. Generation Zero (births between 1998 and now – people too young to remember 9/11) will never know a world in which history is hard to access.

"We access that history with tools that were, almost entirely, the props of science fiction my parents might have encountered – if they read it. My phone is my sonic screwdriver, the internet my TARDIS; these are the tools with which I unlock and manipulate time.

"Take a leap and imagine these tools as a product of sci-fi’s imagined futures. Now think about a future in which we’ve stopped imagining them."

And

Russell Davies's, titled Something About The Lack of Futureness:

"It's hard to miss the missing future in science fiction. Zero History feels like it's set in the past, actually last year, when we were all obsessed with tactical pants and I was still updating EBCB. I went to see Mr Gibson talk last night and he said it might be true that his last three books were a pinhole portrait of the first decade of the 21st century. And it struck me that maybe all his books are that, he's been approaching them from a long way in the past, imagining what they might be like.

"Now he's in them, capturing portraits of the now. Soon he'll be doing history.

"I sometimes think all this talk of atemporality is an abdication of sci-fi responsibility. SF writers seem very keen to deny that they're writing about the future. They're not doing prediction, they're telling us about the now. OK. Well. Pack it in and get on with some prediction.

"Anyway. It's not just sci-fi. I'm also depressed about the lack of future in fashion. Every hep shop seems to be full of tweeds and leather and carefully authentic bits of restrained artisinal fashion. I think most of Shoreditch would be wondering around in a leather apron if it could. With pipe and beard and rickets. Every new coffee shop and organic foodery seems to be the same. Wood, brushed metal, bits of knackered toys on shelves. And blackboards. Everywhere there's blackboards.

"Cafes used to be models of the future. Shiny and modern and pushy. Fashion used to be the same - space age fabrics, bizarre concoctions. Trainers used to look like they'd been transported in from another dimension, now they look like they were found in an estate sale.

Here's Bruce Sterling's most recent set of thoughts about atemporality, much food for thought here, questions from Renata Lemos-Morais at Space Collective ...

A couple of choice morsels to brain-chew:

"There were certainly episodes in the Industrial Revolution when people were agitated about time and space — for instance, anxiety about the disorienting speed of rail travel. However, they had firm ideas about historical development, especially compared to us. A network of the kinds we have today doesn't behave with the comprehensive mechanical timing of a railroad. We have to face new atemporal anxieties, such as the spasms and crashes of microsecond stock-trading, where it's literally impossible to determine what electronic event had strict temporal priority."

"The time compression is certainly part of the issue, but there are also time extensions in network culture. For instance, what is the difference between "the year 1955" and "the year 1955 as revealed to me by a Google Search"? Analog remnants of 1955 tend to be marred by entropy, but digitized clips of 1955 will load with same briskness and efficiency of digital clips from 1965, 1975, 1985 and so forth. In this situation, our relationship to history feels extended rather than compressed, because data from the past feels just as accessible as data generated yesterday. If you are re-using this material to create contemporary cultural artifacts, you don't just get "compression," you also get a skeuomorphism, a temporal creole — a Brazilian anthropophagy when all the decades are in one software stew-pot."

Atemporality, he clarifies, is not about time in some absolute astrophysical sense (which we as human sensoriums and culture/era bound beings cannot apprehend or get near, anyway), it is about culture-time, our sense of how past, present and future relate to each other:

"The passage of time is not a suggestion; time really passes, the days of your mortal lifetime do not return once they pass. If the passage of time was somehow arbitrary, then one would expect to see measurable effects on everyday physics, such as eggs unscrambling themselves, flowing water running uphill, and so forth. I frankly don't expect to ever witness even one of those. Atemporality is about our human, cultural apprehensions and expectations of time; it doesn't refute the laws of cause and effect."

Gibson and Sterling, incidentally, were if not the inventors then certainly the popularisers - with the The Difference Engine -- of steampunk as s.f. breakaway subgenre - steampunk is an early example of an atemporal aesthetic. Here's some images, and then below a few thoughts on steampunk (which is one of the great ommisions from Retromania

When it first emerged, steampunk seemed like it was likely to be just a fad, an offshoot of science fiction that would soon wither. But over the last couple of decades it has bloomed stealthily, establishing itself not just as an active and populous genre of fiction but as a flourishing international subculture. You can go to bars with steampunk décor. The genre has been coopted by Hollywood, as with the recent movie versions of Sherlock Holmes, where the décor and mise en scene is totally steampunk (and quite unfaithful to Arthur Conan Doyle’s original stories). You can dress up in steampunk costumes, go meet kindred spirits at steampunk events, and then invite them back to your house, which you’ve kitted out with steampunk-style knick-knacks and curiosities. In my own home town of South Pasadena, in the suburban outskirts of Los Angeles, there is a steampunk-style antique store only a few hundred metres up the road from where I live, and another that is just a couple of miles away.

Steampunk is an extreme example of a general trend that has swept across the Western world in the last decade or so, and which is particularly strong among the youth: a turning away from the future, what you might call the delibidinisation of Tomorrow. Simply put, the notion of the future is no longer sexy.

postscript: the Prospective 21e siecle sleeve bonanza and its imitator, the science fiction series Ailleurs et Demain

Post-millenial ennui

Dates like “1999”, “2000”, “2001” set off special reverberations-- not just for the s.f. fans among us but for plenty of regular folk too. Even now, when we should have grown blasé about living in the 21st Century, the dates still have a faint futuroid tang that makes the act of, say, writing out and dating a cheque or a form feel slightly eerie, tingling with a poignant trace of what-should-have-been

The future not as impressive and spectacular as s.f.

fans would have hoped

Apparently it’s been proved that there’s a declining

rate of discovery in the sciences.

According to this WSJ blog by Jonah Lehrer, http://blogs.wsj.com/ideas-market/2011/02/07/the-difficulty-of-making-new-discoveries/

According to this WSJ blog by Jonah Lehrer, http://blogs.wsj.com/ideas-market/2011/02/07/the-difficulty-of-making-new-discoveries/

“The most cited studies in a field used to be the product of lone geniuses... but the best research now emerges from groups. One explanation for this shift is the necessity of interdisciplinary collaborations: the most complex problems can no longer be solved by people with expertise in a single field. However, there is another related possibility: science is getting harder. Last year, Samuel Arbesman, a research fellow at Harvard Medical School, published a paper in Scientometrics that documents the increasing difficulty of scientific discovery. By measuring the average size of discovered asteroids, mammalian species and chemical elements, he was able to show that, over the last few hundred years, these three very different scientific fields have been obeying the exact same trend: the size of what they discover has been getting smaller.

[Perhaps the smallness syndrome is the same reason

why we have a plethora of micro-genres and Next Medium-to-Small Things, rather

than major scenes, movements, and Next Big Things]

Lehrer compares to this discovery-declining-rate theory to Tyler Cowen’s idea of a “great stagnation”, which argues that “that our current economic problems are rooted in a larger innovation failure, as the outsized gains of the 20th century (in which living standards doubled every few decades) have given way to a growth plateau... the American economy has enjoyed lots of low-hanging fruit since at least the seventeenth century: free land; immigrant labor; and powerful new technologies. Yet during the last forty years, that low-hanging fruit started disappearing and we started pretending it was still there. We have failed to recognize that we are at a technological plateau and the trees are barer than we would like to think.”

Miniaturization of communications technology

Andy Crouch on how Apple became a kind ofcompensatory religion of futurity, a consoling bastion of measurable progress

in a world otherwise beset by deterioration and malaise

“In the 2000s, when much about the wider world was

causing Americans intense anxiety, the one thing that got inarguably better,

much better, was our personal technology. n October 2001, with the World

Trade Center still smoldering and the Internet financial bubble burst, Apple

introduced the iPod. In January 2010, in the depths of the Great Recession, the

very month where unemployment breached 10% for the first time in a generation,

Apple introduced the iPad.

"Politically, militarily, economically, the decade was defined by disappointment after disappointment—and technologically, it was defined by a series of elegantly produced events in which Steve Jobs, commanding more attention and publicity each time, strode on stage with a miracle in his pocket....

"Apple made technology safe for cool people—and ordinary people. It made products that worked, beautifully, without fuss and with a great deal of style. They improved markedly, unmistakably, from one generation to the next—not just in a long list of features and ever-spiraling complexity (I’m looking at you, Microsoft Word), but in simplicity...

"Steve Jobs was the evangelist of this particular kind of progress—and he was the perfect evangelist because he had no competing source of hope.”

Crouch presents as a kind of privatized version of utopianism or faith:

"This is the gospel of a secular age. It has the great virtue of being based only on what we can all perceive—it requires neither revelation nor dogma. And it promises nothing it cannot deliver—since all that is promised is the opportunity to live your own unique life.... The world—at least the part of the world in our laptop bags and our pockets, the devices that display our unique lives to others and reflect them to ourselves—will get better. This is the sense in which the tired old cliché of “the Apple faithful” and the “cult of the Mac” is true. It is a religion of hope in a hopeless world...

“Steve Jobs’s gospel is, in the end, a set of

beautifully polished empty promises. But I look on my secular neighbors,

millions of them, like sheep without a shepherd, who no longer believe in

anything they cannot see, and I cannot help feeling compassion for them, and

something like fear. When, not if, Steve Jobs departs the stage, will there be

anyone left who can convince them to hope?”

1973 as the Year the Future Died?

The three decades following the end of the Second World War in 1945 had been one long surge of economic growth, technological innovation, and cultural energy, kickstarted by the war itself and its massive mobilization of populations and resources, the state’s vastly increased investment in science and technology, and the peculiar fact that war raises a people’s morale by giving them a sense of purpose and unity (rates of mental illness declines markedly compared with peace time). That postwar surge--and the consensus about the role of interventionist state power, the need for social welfare, and so forth--had begun to falter by the early Seventies.

The fuel crisis of late 1973 was the augur of a massive reality check. Some analysts see that year as the end of a “long Sixties” that began circa 1957. Except that the energies liberated in the post-war period (during which the high metabolic rate of the economy encouraged a mood of future-tilted euphoria and a mania for all things new and progressive) and which reached a climax with the Sixties, didn’t come to a halt punctually in synch with the economic slow-down. There was a kind of time lag, a disparity between economic base and cultural superstructure, which is one reason why the 1970s were a period of such turmoil and polarization. “The left”, understood in the broadest sense, headed further outwards on their trajectory of liberalization and radicalism; the right retrenched in the name of “realism” and the restoration of pre-Sixties morality, a.k.a. family values.

One way of understanding what happened in the Eighties is to see this backlash as partly a delayed response to an economic and sociocultural slow-down that occurred slightly earlier, in the mid-Seventies. Ppostmodernism and retro-recycling ruled popular culture, while politically the presiding spirits of the era, Thatcher and Reagan, were dedicated to restoration of an older order and the rolling back of the gains of the 1960s, a decade they reviled and pinpointed as “where it all went wrong”.

It can hardly be a coincidence that at precisely the point at which both the ideals and the actual gains of the Sixties were being concertedly discredited and undermined, that the Sixties became a presence again in popular culture. Sometimes as empty pastiche (Motown and Stax revivalism of myriad stripes, Prince’s faux-psychedelia circa “Raspberry Beret”, Jesus & Mary Chain), but sometime as surrogate and succor, a wistful harking back to a better time undertaken in impotent defiance of the Eighties (The Smiths, REM and a thousand Byrds-influenced college rock bands)

See also David Graeber's piece for The Baffler, "Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit"

Nostalgia for the future / Baudrillard

Nostalgia for the future / Baudrillard

Jean B saw it as a specifically European malaise: “we are condemned to the imaginary and nostalgia for the future” whereas, he argued, Americans had “realized fiction” and lived in the future, now.

Nostalgia for the future / Pessoa

from page 184 of The Book of Disquiet:

"And yet what nostalgia for the future* if I let my ordinary eyes receive the dead salutation of the declining day! How grand is hope’s burial, advancing in the still golden hush of the stagnant skies! What a procession of voids and nothings extends over the reddish blue that will pale in the vast expanses of crystalline space!

I don’t know what I want or don’t want. I’ve

stopped wanting, stopped knowing how to want, stopping knowing the emotions or

thoughts by which people generally recognise that they want something or want

to to want it. I don’t know who I am or what I am. Like someone buried under a

collapsed wall, I lie under the toppled vacuity of the entire universe. And so

I go on, in the wake of myself, until night sets in and a little of the comfort

of being different wafts, like a breeze, over my incipient self-unawareness**.

Ah, the high and larger moon of these placid nights, torpid with anguish and disquiet! Sinister peace of the heavens’ beauty, cold irony of the warm air, blue blackness misted by moonlight and reticent to reveal stars."

*an alternate version reads: “what regret that I’m not someone else”

**an alternate version reads: “incipient impatience with myself”

One wonder if Pessoa might have been influenced by or had assimilated this passage in J.K. Huysman's Against Nature, expressive of the dandy aristocrat recluse Des Esseintes's revulsion for the modern world of money-grubbing vulgarity, Des Esseintes for whom antiquarianism and exoticism is an expression of his longing to be "anywhere but here, anywhere but now":

"The fact is, when the period in which a man of talent is condemend to live is dull and stupid, the artist is haunted, perhaps unknown to himself, by a nostalgic yearning for another age.

"He bursts out of the prison of his century and roams about at liberty in another period, with which, as a crowning illusion, he imagines he would have been more in accord.

"In some cases there is a return to past ages, to vanished civilisations, to dead centuries; in others there is a pursuit of dream and fantasy, a more or less vivid vision of a future whose image reproduces, unconsciously and as a result of atavism, that of past epochs"

Nostalgia for the future / Buzzcocks

"The fact is, when the period in which a man of talent is condemend to live is dull and stupid, the artist is haunted, perhaps unknown to himself, by a nostalgic yearning for another age.

"He bursts out of the prison of his century and roams about at liberty in another period, with which, as a crowning illusion, he imagines he would have been more in accord.

"In some cases there is a return to past ages, to vanished civilisations, to dead centuries; in others there is a pursuit of dream and fantasy, a more or less vivid vision of a future whose image reproduces, unconsciously and as a result of atavism, that of past epochs"

Nostalgia for the future / Buzzcocks

“Nostalgia

for an age yet to come” figures in the Buzzcocks song “Nostalgia” as a kind of temporal-ontological

disorientation: “about the future I can only reminisce…. my future and past are

presently disarranged… I feel like I’m caught in the middle of time”.

(Apparently around the time of the third album A Different Kind of Tension,

Buzzcocks were taking a lot of acid).

You get similar flavors of profoundly bored restlessness and nameless omnisexual longing in the songs of Morrissey, but in his case mixed up with actual nostalgia in the traditional, past-directed sense. Pessoa's Book of Disquiet, Buzzcocks's songs like "Nostalgia" and "Why Can't I Touch It", Smiths songs like "Still Ill"--these are all testaments of exile. Ernst Bloch, the great Marxist theorist of utopia, writes about "the topically still unidentified no-where whither music leads." Music represents pure transcendence and transport; it's the way out from the drear of here-and-now.

Nostalgia for the future / another, more disturbing

source?

Dominic Gavin

tells me that “In Italy the phrase is associated with

Benito Mussolini who pronounced it in a speech in Milan (I think in 1931),

recorded for posterity by the regime's newsreels; I saw an excerpt in a

documentary. If this isn't mainstream knowledge, it's not exactly obscure

either. In the 1976 elections, the neo-fascist party campaigned with this

phrase as a slogan, by which time it would have acquired an additional meaning.

It's a suggestive phrase in the Italian context, given the amount of effort

that has gone into determining how 'reactionary' fascism was or rather how it

appealed as a narrative of modernization, and so on”

Incidentally, in searching for Mussolini + nostalgia for the

future, I stumbled on this interesting-looking essay that offers a kind of

hauntological reading of Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland, in terms of ghosts of the

Sixties - http://www.themodernword.com/pynchon/papers_berger.html

Futurama

Although it took its name from a pavilion at the New

York World’s Fair in 1939 that was designed by Norman Bel Geddes to look like

the world in 1959, the show’s concept was to fuse the Formica utopia of The Jetsons with the seedy tech-noir atmosphere of Blade Runner.

Retrofuturism

The term "retrofuturism" is said to have been coined by Lloyd Dunn, a

member of the sound art outfit the Tape-Beatles (who operate in a similar

plunderphonic zone to John Oswald) and in

1983 the founder of PhotoStatic

magazine, which four years later renamed itself Retrofuturism.

Dedicated to “the future that never was” : Paleofuture - http://www.paleofuture.com/ - a goldmine of retrofuturisticness!

Dedicated to “the future that never was” : Paleofuture - http://www.paleofuture.com/ - a goldmine of retrofuturisticness!

Retrofuturism:

Donald Fagen’s ‘I.G.Y.”

The wonderfully blithe chorus goes "what a

beautiful world this will be" and the whose verses dream of a time and a place where everything is clean and everyone is

"eternally young."

Retrofuturism:

The Buggles

Partly reflecting Trevor Horn's love of science fiction, from songs like "Living in the Plastic Age" to "Video Killed the Radio Star" (obliquely inspired by a J..G Ballard short story), "I Love You (Miss Robot)" , "Astroboy" and "Johnny On the Monorail".

Retrofuturism in pop culture and pop music / a preliminary attempt at categorization

In music itself,

retro-futurist can refer to a consumer mode of appreciation, the ambiguous

tingles induced by listening to the pioneering synthesizer music of the Fifties

and Sixties, or the Moog-ified easy listening records of Dick Hyman, or the

mega-craze for electronicized versions of classical music triggered by Walter

Carlos’ Switched on Bach.

Retro-futurism can also be a creative sensibility: bands like World of Twist,

Add N to (X) or Ladytron who consciously evoke pop eras that seem full of

wide-eyed futurism, harking back to outfits like the groundbreaking analogue

electronics of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the 1960s, or the glistening

synthpop of the 1980s. In both cases, there’s that bittersweet tinge of pathos,

the hindsight knowledge that these are lost futures. The flourish of futurism

turned out be a fad, not the shape of things to come for all time: pop trends

immediately moved on somewhere else, often back to a more gritty, acoustic

sound (there’s a pendulum-swinging dialectic runs through the entirety of pop

history between plastic/synthetic/artificial/studio-concocted and

rootsy/acoustic/earthy/naturalistic).

What the pop version of

nostalgia for the future harks back to is a sort of future-now feeling induced

by certain electronic sounds--“electronic” understood in the widest sense to

include not just synthesizers but all manner of studio-as-instrument treatments

and techniques, everything from the over-the-top phasing in Sixties

psychedelia, to the syn-drums and vocoders in late period disco, to the gated

drums and Fairlight sampling in much Eighties pop. When these sounds were first

made, they felt utterly of-the-moment and precedent-less; listening, your ears

were tilted to the future, if only because what you were hearing reminded you of nothing. But such

futurity is inevitably transformed into a period signifier within a few

years. Nothing dates faster than

yesterday’s idea of the future. And what

seems to be a herald of things to come in hindsight often turns out to have been

a dead end.

Surprisingly often, when we use the word

“futuristic” to describe a piece of music, we’re talking about music that is

playing with received ideas of the futurist/futuristic. This

“futuristic” already comes with an invisible “retro-” prefix attached.

Just look at Kraftwerk, with their “We Are the Robots” shtick (the band replaced onstage by automatons), their back projected imagery redolent more of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis than NASA in the Seventies. Critiquing the Kraftwerk-indebted New Romantic (a.k.a. Futurist movement) in English pop, which encompassed everything from Gary Numan to Visage, in 1980 Martyn Ware of The Human League declared “it’s a very old fashioned view of futurism, which is like people walking about like Michael Rennie out of The Day the Earth Stood Still. That’s not futurism, that’s more nostalgia than anything else.” But The Human League were themselves a mish-mash of genuine modernism and retro-futurism. The band’s two musicians, Ian Craig Marsh and Martin Ware grappled with the possibilities (and limitations) of state-of-art synthesizers, plunging deep into the technical nitty-gritty of building drum sounds out of blurts of electronic noise. But the band’s image and aura largely stemmed from singer Phil Oakey, a science fiction nut who wrote lyrics inspired by Philip K. Dick and black holes, and from Adrian Wright, a Thunderbirds-fan with a highly developed sense of kitsch, who as Director of Visuals was in charge of creating the slides projected behind the band at gigs.

So what are we actually saying when we talk of music in terms of futurism or say something sounds futuristic? What do electronica musicians mean when they declare they’re “living for the future” (Omni Trio) or boast “we bring you the future” (Noise Factory) or even name themselves things like Phuture? (This “ph”, as used by the inventors of acid house, Phuture, soon became the techno signifier of futurity, a rave code carried on by Photek, Phuturistix, and many more). So much electronic dance music was received and felt and written about as future music. The idea is that the underground is the vanguard, the forward sector of pop music, bringing you right now the ideas that will eventually become the common everyday matter of mainstream pop. But surely, by definition, if these sounds are happening-right now, then how can they be from or of the future? In quest of some kind of clarity, I here sketch a three-way conceptual division:

Futurism

Referring to artists who make an overt ideology out of their aspiration to make tomorrow’s music today, and includes many people in techno, but also groups like The Young Gods, the late Eighties Swiss band who sounded “rock” and had a human drummer but whose actual sound was built from samples of heavy metal, punk, and classical music. Or earlier, the Art of Noise, who pioneered the use of the Fairlight sampler in pop. Both of these groups are not only futurists but have an intellectual debt to the artistic movement Futurism, which AoN make crystal clear with their name, a homage to Luigi Russolo’s The Art of Noises, the musical manifesto of the Italian Futurists.

Futuristic

Describing groups who play with science fiction imagery, an established set of signifiers and associations that relate to a tradition of envisaging (or sonically imagining) the Future. Add N to (X) were notable exponents of this approach in the late Nineties. Scholars of electronic music history, they built their own canon that included the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Throbbing Gristle, Wendy Carlos, and keyboard-dominated prog rockers like Egg, but pointedly excludes Kraftwerk along with the entirety of post-rave electronica. There’s a definite tinge of retro-futurism here, although Add N to (X)’s Ann Shelton characterized the approach as not so much nostalgia as pragmatism, an acceptance that futurism had become its own tradition: “It's a matter of knowing exactly how and what music has ever been made, and knowing what state the music world is in and understanding the futility of trying to do something new as opposed to just doing it without trying.”

Futuroid

Pilfered from “Futuroid”, a track by the hardcore rave outfit Noise Factory, this designates genuinely emergent and unforeheard tendencies in music. In Noise Factory’s case, the futuroid part of their music was the brutally chopped up and accelerated breakbeat rhythms that they and likeminded producers developed in 1992. Why not designate this sort of thing modernist? Well, Modernism is itself a style now, period-bound to the point where there’s such a thing as retro-modernism.

The“futuroid isn’t always necessarily going to manifest in the form we associate with modernism-- starkly functional, stripped of ornament, an aura of bleakness and brutalism, et al. For instance, Noise Factory-style breakbeat science rapidly evolved into a kind of polyrhythmic baroque, while hip hop’s wildstyle graffiti had nothing to do with modernist minimalism but was all garish colors and curlicued folds. In music, we tend to equate “the future” with synthesizers, but what I’m calling futuroid--the truly never-before-heard--is far from the preserve of electronic or computer-based technology. To pick only the most consternating example, I would say that the style of guitar-playing developed by the Edge in the early days of U2 (“I Will Follow” to “With or Without You”) was as futuroid as anything done by most electropop artists at the time (perhaps even more so given that electronic music from Kraftwerk onwards has this patina of received futuristic-ness about it). The futuroid” in music can exist without any of the conventional trappings of the futuristic, either sonically or lyrically or in terms of the rhetoric employed by the musicians.

Pilfered from “Futuroid”, a track by the hardcore rave outfit Noise Factory, this designates genuinely emergent and unforeheard tendencies in music. In Noise Factory’s case, the futuroid part of their music was the brutally chopped up and accelerated breakbeat rhythms that they and likeminded producers developed in 1992. Why not designate this sort of thing modernist? Well, Modernism is itself a style now, period-bound to the point where there’s such a thing as retro-modernism.

The“futuroid isn’t always necessarily going to manifest in the form we associate with modernism-- starkly functional, stripped of ornament, an aura of bleakness and brutalism, et al. For instance, Noise Factory-style breakbeat science rapidly evolved into a kind of polyrhythmic baroque, while hip hop’s wildstyle graffiti had nothing to do with modernist minimalism but was all garish colors and curlicued folds. In music, we tend to equate “the future” with synthesizers, but what I’m calling futuroid--the truly never-before-heard--is far from the preserve of electronic or computer-based technology. To pick only the most consternating example, I would say that the style of guitar-playing developed by the Edge in the early days of U2 (“I Will Follow” to “With or Without You”) was as futuroid as anything done by most electropop artists at the time (perhaps even more so given that electronic music from Kraftwerk onwards has this patina of received futuristic-ness about it). The futuroid” in music can exist without any of the conventional trappings of the futuristic, either sonically or lyrically or in terms of the rhetoric employed by the musicians.

Lillian Roxon writing in 1969 about the future of rock (in Lillian Roxon's Rock Encyclopedia)

Raymond Williams, the godfather of cultural studies, classified cultural artifacts or styles as either residual or emergent. Residual, as you’d expect, referred to tradition, folklore, roots; emergent, equally predictably, designated the progressive, forward-looking, innovative. By and large, music that has any impact on the wider culture beyond the academy or the experimental ghetto necessarily involves a mixture of residual and emergent. Arguably, the futuroid aspect has to be tempered with or grounded in elements of tradition for the music to be enjoyable or even tolerable. A wholly Futuroid music might be as aurally indigestible as Marinetti’s pr oposed Futurist replacement for pasta: a dish of perfumed sand.

The strange thing is that as a fan and explorer of music, I’ve been ardently chasing the sonic equivalent of “perfumed sand” for some years now, seeking out music that presents the utmost challenge to my ability to respond to it as musical. As discussed in this chapter, over the last 13 years or so, with mounting intensity, I’ve become obsessed with the avant-garde classical music of the second half of the 20th Century, the post-WW2 frontier of musique concrete and electronic composition opened up by figures like Karlheinz Stockhausen, the two Pierres (Henry and Schaeffer), Morton Subotnik, Luigi Nono, and many more.

Retromodernism

The Noughties saw a new boom in retro-modernism but the interest was significantly less surface-oriented than the Eighties recycling of Constructivist and Futurist graphics. From endless museum retrospectives of Futurism, Dada, Suprematism, et al, to books like Manifesto: A Century of Isms (an anthology heavily slanted to the first three decades of the 20th Century, what compiler Mary Ann Caws regarded as the golden age of manifesto-making) to conferences like the Tate's late 2009 Don't Look Back: Radical Thinkers and the Arts Since 1909, there has renewed interest in "combative, collective movements of innovation" (Perry Anderson) of the kind that virtually disappeared from the scene with the onset of postmodernity.

I

even toyed with cultivating an interest in modernist churches, from spectacular

concrete cathedrals like the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King in

Liverpool to the common-or-garden New York modernist synagogues and churches

with their abstract-patterned stained glass and iron-twined spires depicting

the play of elemental energies. Los Angeles, being such a relatively young

city, is full of modernistic churches, synagogues and temples of various kinds. Some of them are butt-ugly in the way only a modernist church can be, great cement slabs, and others are cheap and nasty, prefab looking affairs. But there are some genuinely arresting and startlingly stark cathedrals and temples in this city.

Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool, for whose opening Pierre Henry composed Messe De Liverpool

below is Saint Basil's in LA

Left

nostalgia

As if waving a bulb of garlic to ward off the

vampire of "Left nostalgia" (a big no-no in Marxist circles), Hatherley

cites Brecht ("erase the traces") and Benjamin (whose

"Destructive Character" demands "make room" and seeks

"fresh air and open space" through the "clearing away" of

bourgeois culture's clutter of antiques and traditions).

Ruins of radicalisms bygone

The anti-utopian critic Christopher Booker uses the term "nyktomorph" or night-shape, a notion popular with 19th Century Romantic poets, to talk about the way so many people in the Sixties chased the mirage of the new. In his book The Neophiliacs, a kind of obituary for the Sixties, Booker compares nyktomorphs with ruins, that other obsession of poets like Wordsworth: both are expressions of the "the great Romantic emotion of nostalgia, a fixing of the mind on something unattainable…"

Nyktomorphs, in his view, can also take

the form of figments of the paranoid imagination. A blend of

fear-of-dystopia/lust-for-utopia drove some people involved in the Sixties

adventure to terrorism.

Although not as widespread as retro-modernism, you can see the stirrings of a kind of retro-radical chic: movies about the Baadher-Meinhof, novels like Hari Kunzru's My Revolutions, which is loosely based on the Angry Brigade, and Susan Choi's American Woman, written by the point of view of a Weather Underground accomplice. As with virtually all areas of our culture, the web's amateur historians and archivists are documenting every last eruption of radical energy from the last century, with websites detailing the strategic minutiae of the 1984 Miner's Strike, and blogs dedicated to anarcho-punk and organizations like Class War.

Although not as widespread as retro-modernism, you can see the stirrings of a kind of retro-radical chic: movies about the Baadher-Meinhof, novels like Hari Kunzru's My Revolutions, which is loosely based on the Angry Brigade, and Susan Choi's American Woman, written by the point of view of a Weather Underground accomplice. As with virtually all areas of our culture, the web's amateur historians and archivists are documenting every last eruption of radical energy from the last century, with websites detailing the strategic minutiae of the 1984 Miner's Strike, and blogs dedicated to anarcho-punk and organizations like Class War.

As with the enchantment of tower blocks,

I found myself succumbing to a soft-core version of this retro-radicalism

myself when, several years ago, my eye spied some "vintage" political

badges for sale at the community yard sale that takes place annually outside a

neighbouring apartment complex. The

retired couple selling them looking a bit battered by life and I wondered if

they were getting rid of the badges ( which dated from the late Seventies and

early Eighties, causes ranging from anti-nuclear power to opposing US involvement in Nicaragua to

protesting the H-Blocks in Northern Ireland) because they were disillusioned,

all struggled out. I knew there was

something suspect about what I was doing even as I bought half-a-dozen of the

coolest looking badges for a dollar each.

My eye was aestheticising their period aura, the clumsy quaintness of

the agit-prop design, the dourly didactic slogans. I would never have bought the badges at the

time, even though most of the causes I would supported. By the time I got home

I realized I would never wear them in public, even now. That didn't stop me

from picking up another radical retrochic badge several years later, at a

trendy flea market in Brooklyn. Now they

had clearly become collectible, because the price had gone up dramatically: the

cheapest were $3, and so I got just one, Wages For Housework, appreciating both

the bluntly expressed protest against an injustice (something I'd felt since a

teenager, watching my mother's labour) and its utter unrealistic-ness as an

objective (a real shame, as in our home, I do 80 percent of the cleaning).

Cold War Design exhibition

The gist of the exhibition was a different twist on the modernist idea of the inseparability of aesthetics and politics: here it was the superpowers who were jousting, staking the case for which country and creed had the stronger claim to the future. In this contest between consumerism and communism, conveniences versus cosmonauts, the military subtext of the word "avant-garde" (it means a scouting party, whose job is to go in advance of the main army and skirmish, to initiate conflict) emerged in a new light. Modernism resumed in full force after World War Two, but it no longer took the form of signifying epater le bourgeois raids on the mainstream by a marginal elite; it was quite close to the official high culture of the developed world, Western and Eastern. Not only were the would-be revolutionaries of the early 20th Century turned into a new school of Old Masters by museums and curators, dealers and collectors, but the contemporary resurgence of modernist art (abstract expressionist painting, non-figurative sculpture, minimalism and colour-field art) became the preferred decor of corporations and public institutions. And the ideas filtered down into everyday life, merging with the new materials (the ever-expanding array of plastics, fibre glass) and reaching ordinary people's homes in the form of sleek radiograms, streamlined kettles, and elegantly austere chairs. Even nuclear defence bunkers looked cool.

Wandering around Cold War Modern, gawping at, the gaudy whirling kinetic sculptures of Nicolas Schöffer, and the (sadly, mostly on paper) visions of Archigram, it was hard not to feel wistful about this lost future. Particularly affecting were the images of television towers like the Post Office Tower in London and its Eastern Bloc equivalents, which the exhibition argued were the 20th Century equivalent of Medieval cathedrals, expressions of the spirit of the age: a Marshall McLuhan-style techno-mysticism saw in science a kind of unfolding destiny, "an inherent theocratic logic". These thrillingly vertical teletowers were the spires of a secular surrogate for religion: the global village, the world sheathed by McLuhan's "cosmic membrane" of electronic transmissions.

Philips Pavilion / Poeme Electronique

Philips research facility Natlab / Badings, Dissevelt, Raaijimakers

The Silver Records: Philips's series Prospective 21e Siecle

My piece for the Wire on my obsession with Prospective 21e Siecle - the artwork and the music

The holy grail, which came into my hands very recently, thanks to the remarkable generosity of a benefactor

a lot more Prospective 21 e silver sleeves at the end of these footnotes

Collecting post-WW2 electronic and musique concrete